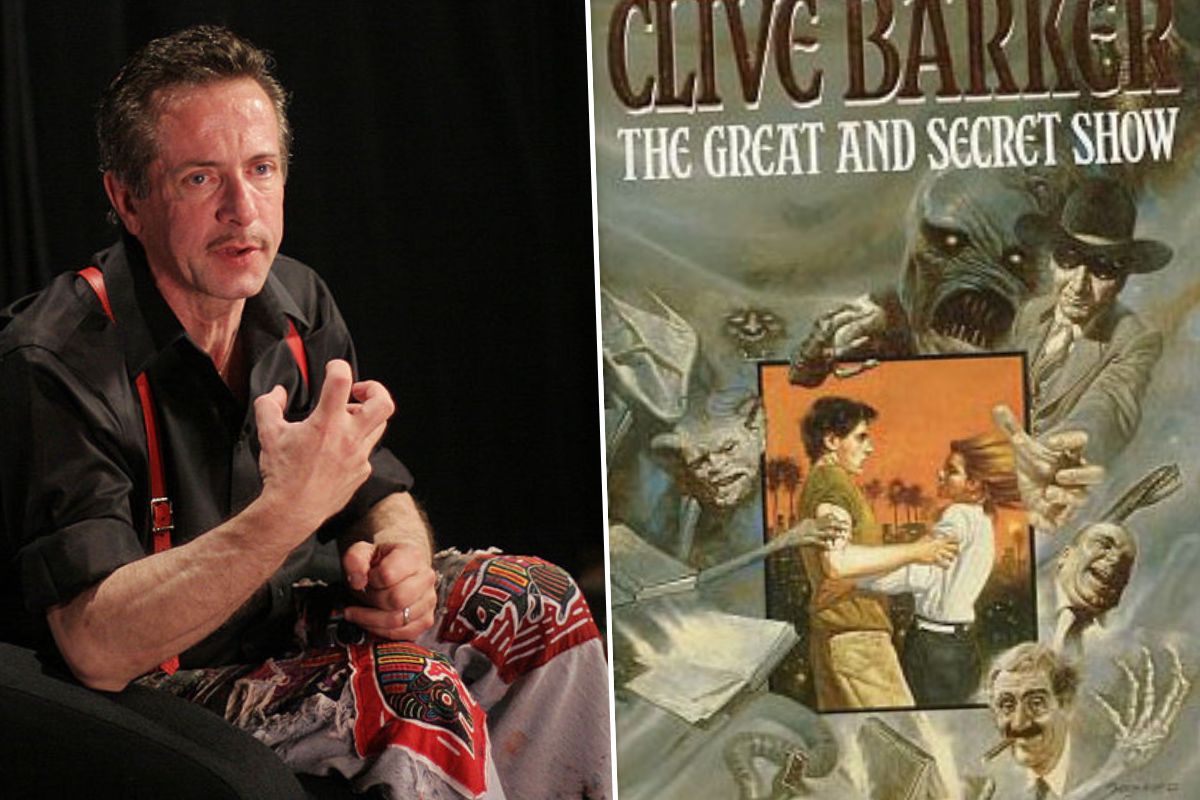

Clive Barker’s The Great and Secret Show

Clive Barker’s sprawling dark fantasy begins in 1969 with Randolph Jaffe, a bored postal clerk, uncovering clues to a secret mystical society known as the Shoal and a hidden power called “the Art.” He teams up with scientist Richard Fletcher, who invents the Nuncio – an alchemical drug that accelerates evolution. After both men consume the Nuncio, they become demigods locked in a cosmic battle: Fletcher turns toward good, Jaffe toward evil. A decade later their conflict spills into a small California town (Palomo Grove). Jaffe (now nicknamed “the Jaff”) raises grotesque creatures (terrata) from people’s fears, while Fletcher sacrifices himself, releasing hallucinogenic energies.

Both have impregnated local women to spawn children destined to continue the feud. Ultimately Jaffe tears open a rift into the dream-sea Quiddity, threatening to unleash the dark Iad Uroboros upon our world. In a metaphysical climax Fletcher’s spirit and other transformed youths (including Jaffe’s daughter Jo-Beth and Fletcher’s son Howard) return from Quiddity to seal the breach and save reality. Barker described this plot as setting the stage for “Hollywood, sex and Armageddon,” a good-vs-evil saga played out in an all-American town.

Major Themes

-

Good vs. Evil: At its core the novel is a Manichaean battle. Jaffe represents unbridled evil (seeking absolute power), while Fletcher embodies reluctant goodness. This contrast is explicit – Barker himself said the story is “still about good v. evil in America” – and the final confrontation in Palomo Grove is literally a pitched war between their offspring’s forces.

-

Transformation & Evolution: Characters undergo radical changes. Both Jaffe and Fletcher physically evolve into near-immortals after using the Nuncio. Their offspring are warped by Quiddity, emerging as “super-children” with mystical abilities. Even ordinary people are transformed: a tabloid journalist and his partner absorb hallucinogenic powers and play hero roles. The novel repeatedly links sexuality and creation; the miraculous births of Jo-Beth, Tommy-Ray and Howard underscore a theme of procreation as magical destiny.

-

Reality vs. Hidden Worlds: A key motif is the veil between worlds. Palomo Grove appears as a mundane Californian town, but it sits atop Quiddity, a dream-sea only accessible at life’s turning points. As Kirkus notes, Barker’s narrative tears aside “the veil between the world of the senses and the world of the imagination”. Strange occurrences (e.g. a ghostly lake, apparitions of past lovers) signify that hidden realities lie just beneath everyday life. Barker explicitly described the novel as about “our dream lives” and an “incalculable evil… moving out of another dimension to invade our reality”.

-

American Culture & Media: The setting and tone satirize Hollywood and mass media. Barker said he wanted to do for “California” what Weaveworld did for Britain, and indeed Palomo Grove’s climax is staged like a freakshow party for movie stars. The story critiques celebrity voyeurism (the reporter builds a career on sensationalism) and even fantasy, as reflected in Barker’s own description: “the book’s about movies, and love. This layers another theme: how American pop culture and consumerism mediate our understanding of the good/evil conflict.

Key Characters

-

Randolph Jaffe (the Jaff): A down-on-his-luck postal clerk who finds secret Shoal letters about the Art. Ambitious and remorseless, he masters the Art and ingests Nuncio, becoming an almost-immortal villain. Jaffe’s body warps into the monstrous Jaff and he commands armies of terrata (monsters born from fear). He even sires children (twins Jo-Beth and Tommy-Ray) to continue his fight. Publishers Weekly sums him up as “down-and-outer” whose hunt for power turns him “evil”.

-

Dr. Richard Fletcher: A brilliant, idealistic scientist addicted to mescaline, Fletcher creates the Nuncio. Initially Jaffe’s partner, Fletcher rebels when he realizes the Nuncio’s corrupting power. He also ingests it, emerging as a superhuman hero. In Palomo Grove he sacrifices himself to seed the final resistance (giving townspeople powers) and imparts knowledge of Quiddity to his son Howard. Fletcher’s struggle with Jaffe (and ultimate self-sacrifice) embodies the novel’s good side.

-

Jo-Beth and Tommy-Ray Maguire: Twin children of Joyce Maguire (Jaffe’s daughter) born from the magical storm. Jo-Beth (twelve) is compassionate and resourceful, Tommy-Ray is fierce and prone to anger. Raised apart (Jo-Beth in a convent; Tommy-Ray on a ranch), they meet only in adolescence and fall in love, unknowingly carrying Jaffe’s legacy. Their bond becomes pivotal: when Quiddity unleashes its forces, Jo-Beth and Tommy-Ray emerge transformed and united, ready to oppose their father’s terrors.

-

Howard Katz: Son of Fletcher and Trudi Katz. Quiet and gentle, Howard is initially raised in Europe and returns to America as a teen. He quickly befriends Jo-Beth and falls in love with her. Howard learns the truth of his heritage and gains insight into Quiddity, which helps him guide the battle’s outcome. In many ways he mirrors Jo-Beth, serving as the counterpart hero from the opposite side.

-

Kissoon: An ancient Shoal master living in isolation in New Mexico’s Loop. He reveals the secrets of Quiddity and the Art to Jaffe (who then betrays him) and later to Tesla. Kissoon claims to guard the metaphysical balance but is himself a dangerous figure; he is later revealed as an agent of the malevolent Iad Uroboros. He wields magic (via “Lix,” a snake-like substance) and seeks to control or destroy Quiddity’s power.

-

Nathan Grillo and Tesla Bombeck: A cynical tabloid reporter and his idealistic girlfriend. They arrive in Palomo Grove to cover odd disappearances. Grillo’s taste for sensational news contrasts Tesla’s empathy. Both become entwined in the conflict: Grillo’s contacts with Terry unfold nightmares into reality, while Tesla, touched by Fletcher’s essence, becomes a conduit for heroic forces. In the climax the couple helps confront Kissoon’s time-loop trap. (Grillo and Tesla exemplify ordinary people drawn into Barker’s cosmic war.)

-

Others: R. Buddy Vance is a minor character (a comedian who dies early, but whose fears are exploited by Jaffe into terrata). Harry D’Amour, the occult detective from Barker’s other tales, briefly appears at the very end to take up investigating the cult of the Iad.

Literary Style and Genre

The greatest show in the world: "The Great and Secret Show" by Clive Barker.

byu/i-the-muso-1968 inbooks

The Great and Secret Show exemplifies Barker’s lush, visceral prose and genre-blending approach. The narrative jumps between horror, fantasy and science fiction with a breathless energy. Early on Barker’s own characters note the tale is “barbaric and baroque,” a description that Critics Weekly observed “fairly sum[s] up the book”. Scenes shift from slasher-esque blood and gore (murders in the postal office) to cosmic metaphysics (time loops, Lovecraftian dream-seas) and erotic fantasy (sexual rituals leading to mystical births). Kirkus praised Barker’s “torrent of invention” – indeed the novel is packed with bizarre, imaginative details (from monsters formed of excrement to psychedelic Hollywood tableaux). One reviewer notes Barker “smears horror and fantasy and science fiction together like clay, or paint on a taut canvas”, capturing how seamlessly he fuses these elements.

Barker himself intended The Great and Secret Show to recapture the grandeur of his earlier work (Weaveworld), promising a “large-scale, ambitious fantasy about good and evil in America” with “the same mixture of the fantastical… and the sexual… and the weird… and the magical and the visceral as Weaveworld”. This baroque, imaginative style is typical of Barker’s late 1980s phase: a focus on grand mythic scope and eroticized horror rather than straightforward scares. (Some critics found this stylistic density excessive – we discuss that below – but fans note the richly descriptive, poetic language and thematic boldness as hallmarks of Barker’s mature style.)

Reception

Critical opinion was mixed. Publishers Weekly found the novel “diverting” but ultimately an overstuffed “potboiler,” arguing that despite its vivid horror imagery the book “fails even to frighten us”. David Foster Wallace (in The Washington Post) blasted it as “pretentious beyond belief,” criticizing Barker’s layered metaphysics and overblown tone. Similarly, Ken Tucker of The New York Times called the novel “skillful and funny but ultimately overwrought,” noting that Barker’s aim to expand horror into “existential despair” was admirable but not fully realized.

Other reviewers were more positive. Kirkus Reviews declared it “Barker’s most ambitious work yet, topping even Weaveworld: a massive… and brilliant Platonic dark fantasy” and lauded it as “one of the most powerful overtly metaphysical novels of recent years”. Horror fans often cite it as a cult favorite for its sweeping imagination and “mind-blowing” concepts. Upon release the book was a commercial success: Barker noted that Great and Secret Show (550+ pages) “went into the best-seller lists” in its first week. In the decades since, some readers have championed it as an underrated epic of horror/fantasy, while others agree with early critics that it remains a dense, polarizing novel. Its status is similar to Weaveworld: beloved by devotees for its ambition, even as its complexity and length draw complaints.

Legacy and Barker’s Oeuvre

The Great and Secret Show is the first volume of Barker’s planned “Books of the Art” trilogy. It introduced the mythic concepts (the Art, Quiddity, the Iad Uroboros) that carry through the sequel, Everville (1994). Everville follows the fallout of this novel: it deepens the lore of the cosm/metacosm and brings characters like Harry D’Amour into the narrative. Barker has said these novels use magic as a metaphor for creativity and imagination – indeed, some critics compare the series’ scope to Tolkien’s epics. In that sense, The Great and Secret Show stands at a pivotal point in his work: it shifts Barker from pure horror toward mythic fantasy-horror hybrids. It also foreshadows his later motifs of blurring art and life; as Barker himself quipped, he wanted to do for American pop culture with The Art what Weaveworld did for British folklore.

Beyond the novels, the story has had other incarnations. In 2006–07 IDW Publishing adapted it into a 12-issue comic series, expanding Barker’s imagery into graphic form. Although Barker later focused on children’s fantasy (the Abarat series) and other projects, Great and Secret Show remains central to his bibliography as a flagship of his late-’80s vision. It epitomizes Barker’s themes of hidden realities, erotic creativity, and metaphysical horror, bridging his early dark fantasy (Books of Blood, Weaveworld) with his more overtly supernatural later work (Imajica, Coldheart Canyon). For horror and fantasy readers, it remains an audacious, if divisive, epic that showcases Barker’s singular imagination and his drive to push the genre’s boundaries.